- About

- Solutions

- Essentials

- Utilities

- Publications

- Product Delivery

- Support

In the early 2000s, the Gartner Group coined the term zero latency enterprise (ZLE). In its words, ZLE was “the instantaneous awareness and appropriate response to events across an entire enterprise.” This response was later renamed the real-time enterprise (RTE).

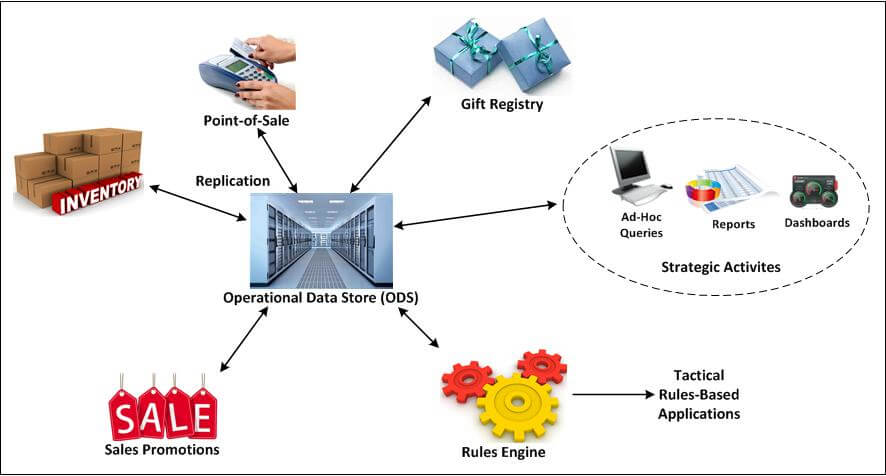

Figure 1 shows an operational data store (ODS) network, with bi-directional arrows representing the flow (replication) of information between the ODS and point-of-sale (POS), gift registry, inventory, strategic activities for a decision support system (which includes ad-hoc queries, reports, and dashboards), sales promotions, and rules engine (which sends the data to tactical, rules-based applications). In this architecture, any application can publish, subscribe, request, and reply to the ODS, which consolidates, extracts, and transfers rich, up-to-date information from any other part of the network.

Figure 1 — The Operational Data Store

HPE was a leader in ZLE, with its ZLE architecture centered around an operational data store (ODS) that was similar to the data store used by an online data warehouse. Rather than periodically loading the ODS with massive amounts of data via an ETL facility, the ODS was trickle-fed transactions as they occurred so that it always contained the latest state of the enterprise as well as historical information. Using the ODS, classical data-mining engines could generate strategic information and knowledge, and real-time rules engines could make tactical decisions regarding immediate actions to take.

One particular ODS characteristic requires it to handle mixed workloads. On the one hand, it must be able to respond to complex queries from knowledge users, data-mining facilities, and rules engines using online analytical processing (OLAP). The database structures suitable for OLAP are characterized by fat keys that allow rapid searching of the database to respond to complex queries. On the other hand, the ODS must be capable of online transaction processing (OLTP) at an extremely high transaction rate, as it is being fed transactions in real-time from many enterprise systems. The database structures suitable for OLTP are characterized by skinny keys that require a minimum of updating as data is added to the database.

Another particular ODS characteristic is that it is bi-directional. Unlike a data warehouse, which typically only accepts information from enterprise systems, an ODS both accepts information from and delivers information to the other enterprise systems. An example of this characteristic is the act of keeping databases in synchronization. A particular data item, like a customer’s address, may be stored in several databases around the enterprise. If one system changes this data item, the ODS acts as a central data repository that informs the other systems of the new data value so they update their databases.

Other examples of outgoing information are the results of the rules engine. If the rules engine decides to recommend a particular immediate action, that action is communicated to the appropriate enterprise system for execution. For instance, if the rules engine for a credit card processor detects suspicious activity, it immediately alerts the authorization system to take appropriate action.

In concept, the ODS, which contains all of a corporation’s data, could become the database of record, the single version of truth. This action generally does not happen because of regulatory requirements and other considerations and the database of record remains on the existing systems, where it was resident for decades.

As previously described, the ODS is simply the RTBI system but extended to the enterprise. Though RTBI systems are becoming common today, full-blown ODS systems have yet to make a significant appearance due to the complexity and cost of designing and building such far-reaching systems.

![]() White Paper: The Evolution of Real-Time Business Intelligence

White Paper: The Evolution of Real-Time Business Intelligence

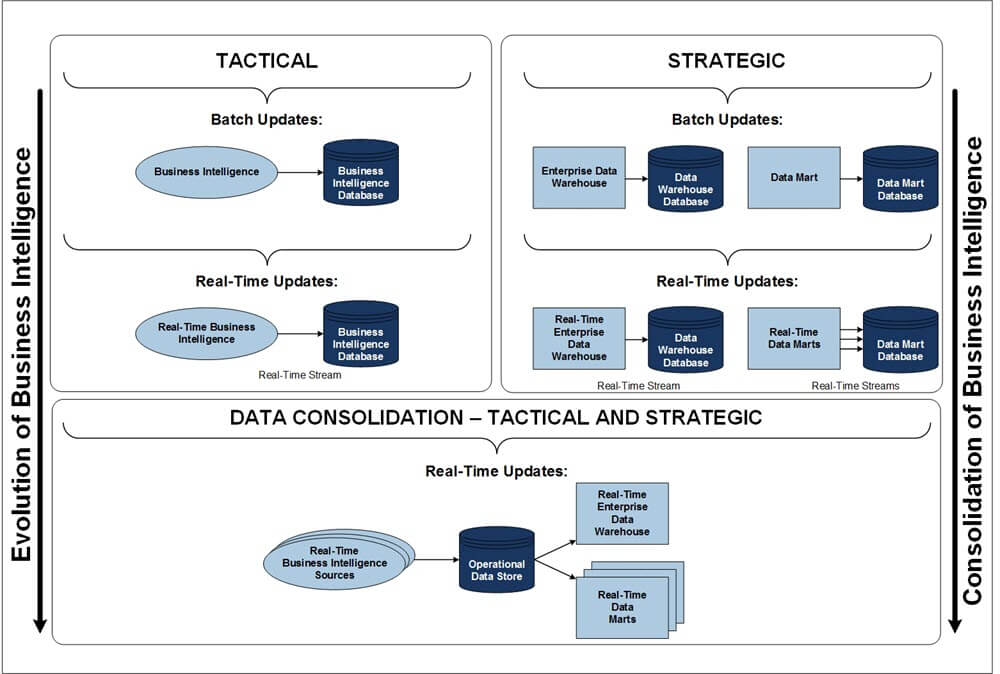

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the ODS, from its early stages (top of the diagram) to data consolidation (present day, bottom of the diagram). In its early stages, an ODS consisted of separate tactical and strategic systems, populated via periodic batch updates. These systems evolved into real-time systems, with ODS data being updated as it was changed on source systems, but there were still separate tactical and strategic systems with multiple ODS databases. There was no single, consolidated view of the enterprise. At the bottom of the figure, data from all these multiple ODS sources is consolidated in real-time into a single, true ODS, driving all the tactical and strategic decision making across the enterprise.

Figure 2 — Consolidation and Evolution of Business Intelligence

It is conceivable that RTBI systems may evolve eventually to ODS systems. Early dedicated business intelligence systems used online data warehouse or EAI technologies. As these technologies proved their worth, data replication was added to move the technologies to real-time business intelligence, real-time sales analysis, data insight, and business insight systems, thus expanding their reach. Though RTBI systems exist today in many applications, each RTBI system generally supports a single purpose such as fraud detection, instant customer promotions, or just-in-time inventory.

![]() Case Study: Real-Time Credit and Debit Card Fraud, an HPE Shadowbase Real-Time Business Intelligence Solution

Case Study: Real-Time Credit and Debit Card Fraud, an HPE Shadowbase Real-Time Business Intelligence Solution

Considerable effort was invested by some companies to consolidate a multitude of RTBI systems into a single ODS supporting enterprise-wide tactical and strategic decision-making or enterprise content management (ECM).

The advantages of such integration are clear:

However, so far the obstacles to achieving this goal have been daunting. For instance:

The bottom line is that today, companies are achieving RTBI by directly integrating their systems using real-time heterogeneous data replication, or they are trickle-feeding data marts in real-time and using these marts to gather information. These warehouses or application networks may or may not turn into an ODS as consolidation occurs. If no warehouse currently exists to act as the stepping stone to an ODS, companies may find it more economical to simply interconnect their systems in a mesh network using existing EAI technologies, instead of following a more planned and fruitful, but expensive path to an ODS.